ARTIST INTERVIEW: CHRIS AGNEW winner of the Derwent Art Prize 2016 People's Choice Award

Posted by Cass Art on 26th Feb 2018

Chris Agnew is a multi-disciplinary artist and winner of the People’s Choice Award as part of the Derwent Art Prize 2016. We caught up with Chris to find out more about his practice.

The 2018 prize is now open for entries, find out more about the prize and how to enter below…

Why did you choose to enter the Derwent Art Prize 2016?

Forming an opinion about a work in a vacuum can be problematic in my experience. How I feel about a piece hung on my studio wall or even in a solo show, can be pretty different from when I see it amongst other works in a group show. Having been included in various prizes over the years has always allowed me to take a step back and see the work in a new light.

You know when you buy a leather jacket and parade round the house thinking that you’re pretty much the coolest person in the world? Then you take it out for a spin at a party and see everyone else’s leather jackets. It’s only in that context that you can really judge how cool your leather jacket is; if it suits you, if it operates in the way that you want it operate, if all your other jackets now look dull in comparison, or if you should have just stuck to tweed like your mother told you. It’s something like that. With free drink.

I also really appreciated the fact that people voted for my work to win the People’s Choice Award, so if you’re reading this and you voted for it, many thanks to you.

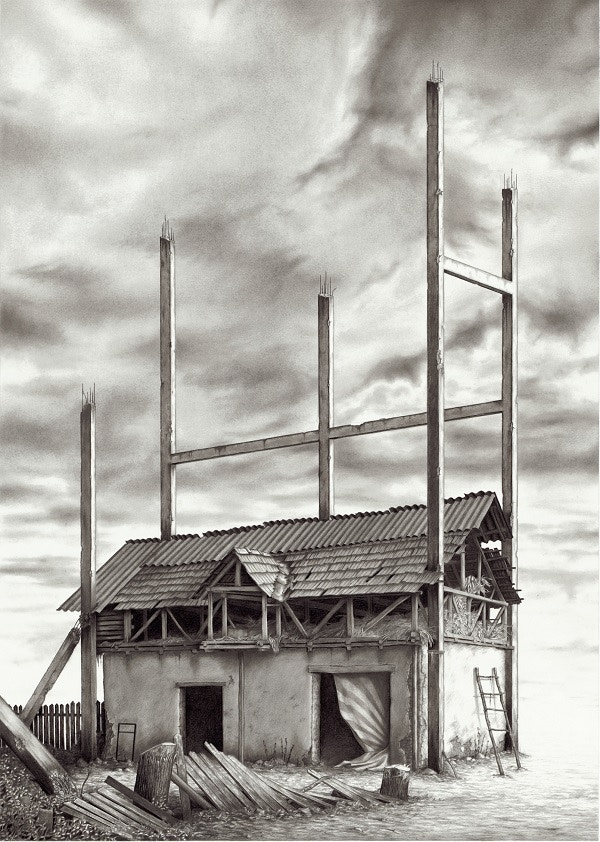

Tell us a little about 'No Word of a Lie', the graphite on paper piece that was shortlisted for the latest edition of the Prize.

The image is a composite of a few photographs that I’d taken whilst on a field trip to a town called Valenii de Munte, a couple of hours outside of Bucharest in Romania. The research was part of an on-going project with Casa Jurnalistului, a collective of independent journalists in Bucharest who work on in-depth features about social issues in Eastern Europe. They have some incredibly insightful articles about the region published in English on their site. Go read: casajurnalistului.ro/eng

When I first moved to Bucharest in 2011, I bought an antique writing desk at a flea market. The guy who sold it to me said that there was something rattling around in the locked drawer but that it was included with the desk whatever it was. The drawer revealed an entire family history dating from 1919 to 1989; photographs, personal letters, official documents, money, and amongst many other items, the suede case for a small handgun. After translating my way through the material with the help of the journalists, and some fairly dodgy detective work, I managed to track down the family and have been conducting interviews with them about their history. The story has taken some pretty unexpected turns – haunted graveyards, a Communist assassination, 1960’s New York, political corruption – so I’m spending some time plotting the precise route in which to take it. The project won the inaugural Axisweb Artist Award last year and they have been great (and very patient), acting as a sounding board for my ideas and providing support along the way.

The slippage between fact and fiction has always played a major role in my practice, so the title of the drawing ‘No word of a lie’, is a play on this.

Methods of researching, disseminating and re-purposing knowledge lie at the heart of your practice: what is it about drawing as a process that enables you to explore and express these?

My sketchbooks are actually filled with writing rather than drawings, because I don’t really think in images, but in ideas and processes. When a composition starts to ooze out of my writing though, that’s when I’ll quickly turn to drawing to capture it. The immediacy and versatility of drawing allows ideas to be communicated across linguistic barriers faster than most mediums. Drawing has the ability to evolve with each generation of artists, whilst still retaining the universal principles exhibited when the first humans blew pigment against their hands on cave walls. If you imagine the history of drawing as a vast family tree, I think it’s easier to jump around the branches in order to trace your own DNA than it is in most other mediums.

A pencil line on a white blank page is like a zero point, where as a painted line is arguably already loaded with the connotations of the colour you choose, the width of the brush, what medium you’ve used etc. I’m not saying that’s a more or less desirable quality of course, but that’s how I understand drawing in relationship to other mediums.

Your output includes drawing, painting, film, floor and furniture design as well as a unique engraving technique involving gesso panels and oil paint. To what extent do these processes influence each other or combine within your practice?

I had a solo project at London Art Fair at the start of last year for which I made a floor. I sourced an old parquet floor on eBay which I sanded, charred, and inlaid with brass strips. The work started a whole load of conversations with people about what it was exactly. First they wanted to know if they could walk on it, which of course they could, then they wanted to know if it was a sculpture, an installation, an engraving or what have you. I could only really reply that it was an artwork that you could walk on, that had been designed to be taken apart, transported, and put back together to be exhibited somewhere else. Defining what it is in such strict terms is not so important to me.

I’ve always enjoyed the misdirection and trickery of some processes, how you can push a medium to the extent that you don’t know if it’s one thing or another, so it loses those medium specific shackles and functions outside the boundaries of ‘how to read a painting, or ‘how to read an etching’. There is a fine line (pun intended) to this though. If the illusion is too successful, then the viewer might not realise that there is a subject that needs interrogating, thus rendering them passive rather than active, which is never really what I’m after. I’ve had quite a few panel etchings in printmaking shows over the years, but aside from the fact that the mark-making technique is similar to drypoint etching, the works aren’t actually prints, nor are they capable of yielding any prints. Finding a term that describes them has always been difficult, because they are neither one thing nor another. They’re like a wolf in sheep’s clothing, pretending to be a dragon. Something like that.

What’s important though is that they all feed into and off each other, in some great orgiastic co-existence that’s intent on moving in the same direction.

Is there a particular drawing practitioner who inspires you or who has influenced your practice in some way?

One show that always sticks in my mind was Pavel Pepperstein’s room at the Victory Over the Future show in the Russian Pavilion at the Venice Biennale in 2009. The room was painted black, lit with UV lights so that the drawings glowed on the walls. The room was pumping with this soundtrack of Pepperstein himself rapping over Stravinsky’s ‘The Rite of Spring’, with phrases like ‘hey Western teacher, leave our kids alone’, and ‘the black square, on the red square’ (you can find the soundtrack on youtube). There were so many different access points to the work, and one person could leave with something entirely different from the next. The works themselves weren’t necessarily a direct influence on my practice, but it was like a shot of adrenaline direct to the heart of drawing.

I don’t necessarily look at drawing practitioners to think about drawing though, but a few that come to mind at the moment; Julie Mehretu, Ciprian Mure?an, Lucy Skaer.

Reading through the range of projects that you have been involved in, it seems that you are keen to seek out collaborative artistic experience. How do you see the value of collaboration, both on a personal level as something that influences your own practice, and on a universal level as something that may influence the dynamic of the contemporary art world?

Collaboration can be extremely valuable when it is the right approach for a specific project, however I’m always wary of collaborative projects just for the sake of collaboration. Some ideas flourish and expand in unexpected directions when there are multiple voices, but some can become clunky and contrived.

If the subject matter requires some form of interdisciplinary exchange, cross-cultural dialogue, or just a game of cerebral ping-pong between two like-minded artists then that’s great. It’s always nice to have lunch with someone. If the work requires you to spend 6 months in a room on your own however, then that’s how it has to be. In terms of my collaborations, I wouldn’t say that I seek them out especially, but that some of the projects I choose to work on require an element of collaboration so that I don’t become the dictator of the material, shouting it down when it should be standing tall on its own.

Speaking of collaborative projects, tell us about the one which saw an archaeoastronomer inviting you to a remote Pacific island to watch the final solar eclipse of the Mayan Calendar.

I’ve always been interested in the idea of the investigation, the search for a particular truth, fact, culprit or what have you. The investigative process can lead you to such absurd places that an idiosyncratic vernacular is almost an inevitable by-product. I started participating in online forums discussing apocalypse theories whilst on my Masters course, and built up a rapport with a Canadian archaeoastronomer. In 1996, he was rambling around Robinson Crusoe Island, 700km off the coast of Chile, when he stumbled on a giant megalith that resembled the face of the Mayan Sun God. After calculating its location, he realised that this was the only vantage point in the Western hemisphere where you’d be able to witness the planetary alignments that were to bring about the end of the Mayan Calendar. His theory was that the Mayan’s had actually visited the island to carve this monument to the end of the world, and this is what he was trying to prove. Some people believed that these planetary alignments would signal the end of the world in 2012, but the Mayan Calendar is actually a wheel so it just rolls over and starts again. Western culture is hooked on this teleological approach to and understanding of society and civilisation, which is what I was kind of exploring with the project. After a lot of emails being exchanged, he finally invited me to the island to watch one of the solar eclipses with him. I really couldn’t turn down an invitation to watch the end of the world.

For my degree show, I only exhibited a 3 minute film on a loop and a large etching in resin directly opposite, but I was pretty much a feature in the space regaling the visitors with the tales of the expedition. I was reading a lot of Joseph Campbell at the time and the project took on this guise as the archetypal ‘hero’s journey’, so it became something that everyone could relate to in some way because it is so deeply engrained in all of us. It lives in everyone’s dreams.

See more of Chris Agnew's work on his website here.

ENTER THE DERWENT ART PRIZE 2018 BY 5PM ON 8TH MAY 2018

The Derwent Art Prize aims to reward excellence by showcasing the very best 2D & 3D artworks created in created with any pencil or coloured pencil as well as water soluble, pastel, graphite and charcoal by British and International artists. A total prize fund of £12,500 will be awarded at the Private View at Mall Galleries, London in 2018. Find out more here.

Image credits:

Untitled (floor): Charred reclaimed parquet floor with brass inlay, 484 x 300cm, 2017

No word of a lie: Graphite, 58 x 82cm, 2016

Five can not: Oil paint on carved pigmented gesso panel, 86 x 61cm, 2017

Between the takes: Oil paint on carved pigmented gesso panel, 49 x 35, 2018

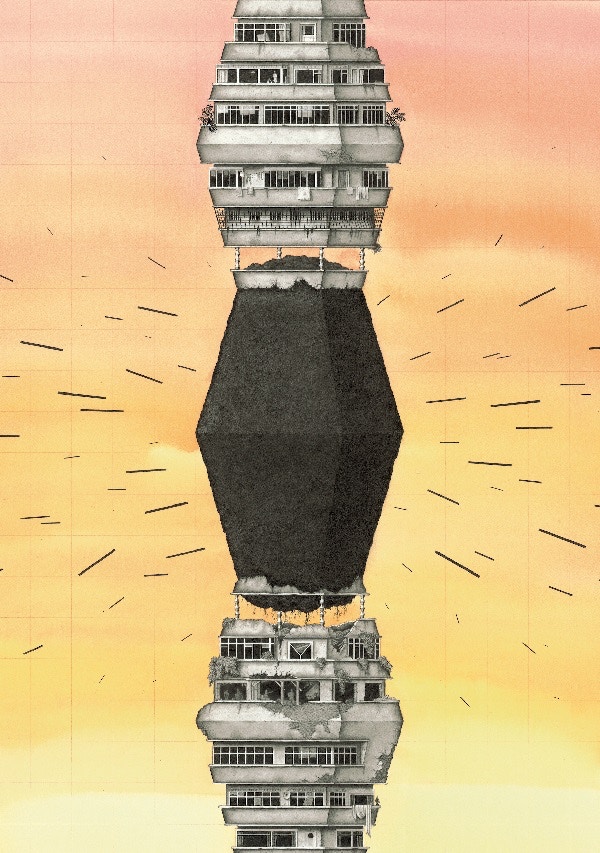

Ba da, Doda (Cogent black mass): Pencil and watercolour on archival paper, 30 x 42cm, 2017