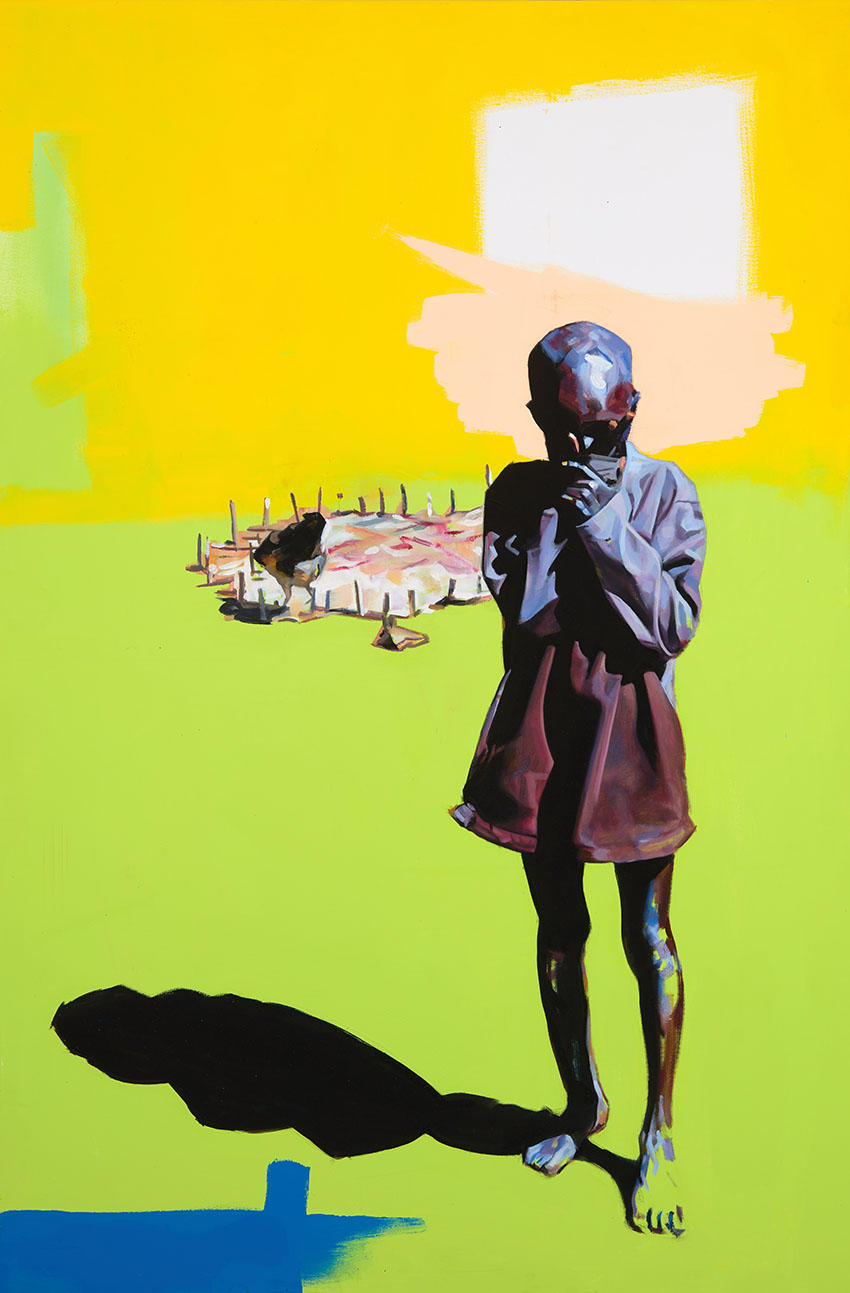

Multidisciplinary artists Aaron Bevan Bailey was born in Peckham south London, of Jamaican and Scottish heritage. His paintings reflect having to negotiate ever changing boundaries of race, environment, identity and anonymity. The work seeks to explore the fractured connection we experience in modern society.

Hi Aaron, really appreciate you taking the time to speak to us today. Firstly, can you tell us what drove you to be an artist?

I can’t remember not being an artist, my earliest memories are lying on the floor sketching in a colouring book. Art or creativity for me is a need to create order out of chaos. Maybe not order exactly but to curate chaos into something I can make sense of and relate to. For me, paintings feels like an itch being scratched. It is a language without words where I can convey much deeper emotions than I could verbalise.

In your work you paint the part of people that recalls spiritual connects even if they cannot see it themselves. Can you elaborate on this and how you encapsulate

In my work I try to catch moments that are fleeting, unconscious. In my past series of portraits “between spaces” I painted people sleeping on London public transport. It felt like in these moments people momentarily took off their armour against the city and you could see their inner vulnerability. Being stuck in a metal tube underground with hundreds of strangers is such an unnatural environment people close their eyes and go into sensory shut down for self preservation. I was fascinated by where people go in this half waking state. With portraiture I feel it is not enough to paint the likeness of someone. If you want to create an image that connects with people you have to capture someones essence.

In my most recent series “Samburu” I went to stay with the indigenous Samburu Maasai in Kenya. This was the opposite. Instead of people cut off from their spirituality trying to block out an unnatural system, I found people living in their right relationship to nature in constant spiritual connection through ceremony.

Your work has such a unique aesthetic to it, with large swades of colour with power figures sometimes in isolation in the foreground. It seems you’re combining traditional painting methods with a contemporary twist. Could you tell us how you developed this such distinguishable style?

My large areas of flat colour are something that developed fairly recently. I was trying to create a form language that I felt symbolised the simplicity and vibrance of the Samburu way of life. They have an oral tradition meaning Mar, their language, has no written characters. They don’t have pictorial art either. Their nomadic way of life means they can only collect what they can carry so decorating themselves and each other became the art. The areas of negative space in my figures in this series represents a sort of cultural erosion in the wake of colonialism. I wanted to avoid the tourist brochure image of the Samburu and paint the person inside not just a romanticised costume. Forces out of their control conspire to end their traditional nomadic way of life. Not least the smart phone itself in one way connecting them to the modern world in another plugging them into the capitalist nightmare we live in and making them forget their traditions and values.

The colour was also like a form of therapy for me during the pandemic, I would paint these big blocks of colour in my studio not knowing exactly what they would turn into. There is something childlike and sensual in colour, for most of us it is the first language we learned to understand. A lot of the time I am trying to simplify and make combinations that would appeal to my 5 year old self. I also love artists like Mondrian and the pop art movement. I love that simplicity when it comes to colour. It’s the same saturation that makes us stop and look at advertising used to sell an idea rather than a product.

“People are just a collection of stories that they tell about themselves when you remove that fragile perception of self you make room for a much deeper sense of connection awareness and understanding to happen.” - Aaron Bevan Bailey

If we were to wander into your studio, in terms of materials what would be your go to’s and why are these important to your practice?

I love oils, the depth the way they mix into each other and the richness of skin tones you can get with them never gets old for me. Recently I have been using a lot of the “So Flat” range from Golden paints which has an ultra matt finish. I really enjoy the juxtaposition between the rich oils and the bold matt colour.

So along with being an established painter, you’re also a photographer and director. Do these different disciplines cross over in some ways, does one influence the other or do you treat them as separate disciplines?

I feel they all flex the same muscle in different ways. I am always trying to infuse one with the other. My favourite photographs I take are ones with implied narrative. Like if you shut your eyes you could unpause them and imagine what happened next. I do a lot of life drawing which I think directly improves how I take photographs, its made me consider angles and lighting differently. I’ve worked as a production designer, when I am making films I am trying to paint in the frame. I also storyboard a lot of the film projects I make so I literally see those images come to life.

You spent quite a lot of time in Kenya which inspired an incredible series of works. What was your experience like and how did It impact your practice?

Going to stay with the Samburu was a spiritual awakening for me. I saw how as human beings we have the potential to live with such grace and gentleness. Respecting nature and existing as its custodians rather than exploiting it for profit. It felt like something I had been looking for my whole life but never found in Europe. It reaffirmed my faith in humanity knowing that we originally lived by these tenants, we have just unlearned them. It gave me hope.

You documented the Black Lives Matter in 2020 which must have been such an incredible harrowing moment in time. How did you find this experience?

It was a very emotional time, the lockdown turned up the volume on George Floyd because we were all stuck inside glued to our devices. It felt like a rejection of the old ways not just from black people but by British society as a whole. It was as if it gave people permission to look inward and examine their own implicit bias and prejudice. Taking photos at the protests was interesting, I had all but stopped doing street photography because peoples faces were always covered and I found the mask quite a depressing symbol. It seemed to have the opposite effect at the BLM protests, it concentrated peoples emotion into the eyes. I feel some of those image are the most powerful I have taken.

Finally and thanks so much for talking to us Aaron, what has the rest of 2022 got in store for you that our audience can keep an out for?

Im working on a new series of portraits at the moment and writing a screenplay. I currently have an exhibition on in the Hoxton Hotel in Holborn in conjunction with Saatchi Art and The Other Art fair that is on till the end of the year.

BE SURE TO CHECK OUT AARON'S WORK ON HIS WEBSITE AND BE SURE TO FOLLOW HIM ON INSTAGRAM @AARONBEVANBAILEY

Add To List

Add a Wishlist

form to add wishlist here