ARTIST INTERVIEWS: WINNERS OF THE LONDON INVITATIONAL 2025

Posted by Galeria Moderna on 11th Dec 2025

In this guest blog with Galeria Moderna, we step behind the scenes and into the creative minds of the eleven selected artists of the London Invitational Art Contest and Exhibition 2025 at Galeria Moderna’s Summer Southbank Exhibition. Discover the insights, techniques, and personal stories that shaped their remarkable works.

Whether you’re an emerging creator or simply curious about the craft, we hope their words spark fresh inspiration on your own artistic journey…

Summer Exhibition at The Sidings Waterloo Southbank London

STUART ALAN GREEN: CASS ART AWARD

Congratulations, Stuart! Your work often begins with simply being present in a landscape, then evolves into a deeper exploration of the marks left by both nature and humanity. How do you recognise when a place is inviting quiet observation versus when it pushes you toward uncovering hidden layers of story and history?

This is a difficult question to answer because so much of the response is based on gut feelings. There are so many sights and views that inspire. It could be a line of trees or hedgerow patterns. It could be eroding and peeling paintwork on a building. It could be early morning mists revealing rolling hills or fenland waterways. More likely it would have some sort of inherent grid, repetition or patchwork feel. The key thing is that something about the observation lights the touch paper towards creation.

You build your paintings using oil pastels and oil bars before layering oil paint with palette knives and scratching back into the surface. What role does this physical process of layering and revealing play in expressing the textures, erosion, and rhythms of the land itself?

The farmer physically changes the earth through ploughing and planting, creating different textures, colours and patterns. In simple terms, I use the same process of scratching, revealing and altering the surface of the painting. Throughout my teaching career I have always tried to put students out of their comfort zones, and I now do the same with myself almost attacking the canvas. Not what I was taught at art school but I find the physicality of the process energising and more creative.

Your practice is rooted in discovering colour, pattern, and form within real environments. Are there particular locations or recurring landscapes that continue to pull you back creatively, and what keeps those places alive as sources of inspiration over time?

Time spent teaching in Australia changed my life and perspective quite literally, when flying from England’s green and pleasant land to an explosion of colour. I have been lucky enough to travel widely and this has been very important in my development as an artist. Travel has broadened the palette and challenged my perceptions. I regularly visit the Peak District and I do enjoy sitting on limestone ridges drawing the beautiful patchwork of fields. One of these days I will get it right!

You describe experiencing “exciting dynamics and surprises” as you work back through layers of paint. How important is unpredictability in your creative process, and do these unexpected moments help shape meaning within the final piece?

I try and paint with a sense of freedom and a mindset of accepting the happy accident. Serendipity is important to embrace for it helps the journey of the painting to be fresh and non formulaic. It's all part of the journey in search of a voice.

ANNA CLEMENT

Congratulations Anna, you are a self-taught artist with a love for expressive colour. How did you find your artistic voice, and what moments helped shape the bold, distinctive style you are now known for?

My artistic voice is not something I set out to develop, it simply emerged, like handwriting. With no formal training, my process is spontaneous and intuitive rather than formulaic. I choose colours instinctively and adjust them as a painting evolves, sometimes enjoying the happy accidents and randomness created by this approach. I think that my love for the Impressionists is definitely reflected in my work, especially Van Gogh, whose emotional intensity, bold brushstrokes and use of colour resonate strongly.

Your selected piece “The Cottage Garden” draws viewers through layers of colour and bloom toward a hidden home in the distance. When building a scene like this, do you begin with an atmosphere, a specific memory, or a visual rhythm in nature?

I am constantly inspired by flowers and gardens, photographing them wherever I go. Each painting begins with a desire to share the fleeting beauty of Nature, be it a shimmer of light, a shift in season, or the rhythmic patterns made by different blooms. The Cottage Garden was created to evoke memories of a beautiful scene into which I want the viewer to be fully immersed. Not only do I want them to see the colours, but also feel the warmth of the sun, the summer breeze and smell the scent of the flowers.

You move fluidly between landscapes, seascapes, and portraiture - including pets and people. What draws you to such a wide range of subjects, and how does your approach shift depending on who or what you’re painting?

I paint many subjects to keep learning, as each one teaches me something new. Landscapes let me paint freely, while portraits demand focus and precision to capture likeness and spirit. Moving between the two keeps me balanced - one nurtures my intuition, the other my discipline. Together they deepen my understanding of what painting can express.

Your work bursts with energy through oil paint, particularly in floral scenes where pattern and colour collide. How do you balance realism with expressiveness to ensure viewers don’t just see the garden, but feel the summer day within it?

Balancing expressiveness with realism is a constant tension. I often worry that my work looks unfinished: too loose, too many repeated rhythms and patterns and not enough detail. Yet I love the unpredictability of creating quickly, without overthinking, throwing colours on the canvas, letting them merge and watching patterns emerge. That spontaneity is my excitement made visible, and hopefully imbues the paintings with the energy and life that I want the viewer to feel.

ASYA DUDKO

Congratulations on your win, Asya! Your work is deeply influenced by the mystery of life and the unknown — how do you decide which hidden story or concept will take shape in your next piece, and at what moment do you feel the story begins to reveal itself through the form?

Life is full of mystery, and it is this sense of the unknown that fascinates and inspires my art. Through my sculptures, I explore contradictions: things that cannot exist together in reality but find harmony within my work. My characters embody the belief that anything is possible: a Snowball Collector who preserves the snowballs and keeps them forever, an Unknown Soldier who achieves the impossible, or Moonlight Birds that carry messages from distant worlds.

Each sculpture carries its own concept and story, often revealing itself gradually. Sometimes the idea arrives fully formed; other times, it takes shape during creation, as if the work itself begins to lead the process. For me, the visual form is the key to unlocking meaning, yet every viewer brings their own interpretation. My goal is to touch hearts and awaken emotions that lie quietly within the soul.

Your practice blends figurative sculpture, relief panels, and painting, often using unique materials such as Paperclay and vintage objects. How does working across dimensions and materials help you express layers of meaning or symbolism within your narrative themes?

Though these forms differ in medium and dimension, they all share a figurative essence and a stylised interpretation of reality. Working across materials allows me to explore my ideas more deeply and develop the stories behind each artwork. The theme of family, for example, began as a sculpture series and later evolved into larger relief panels. My experience with oils and acrylics has shaped the unique finishing technique I now use on my Paperclay sculptures, which are modelled over wire armature and brought to life through texture, colour, and form.

Coming from a rich Russian cultural background and later building your creative career in the UK, how have these two worlds fused in your artistic voice — and do certain colours or motifs speak differently from each culture?

My cultural background has always been a source of inspiration for me. Objects such as keys, wheels, and bells, as well as motifs like birds, fish with human faces, and winged figures, are all drawn from Russian legends and fairy tales. These motifs symbolise spiritual and eternal ideas, complemented using blue and its contrast with red: colours that have traditionally represented divinity and the heavenly realm in Russian culture. While I recognise that each culture has its own symbols and interpretations, I believe that these eternal concepts are universal and speak for themselves.

You’ve not only developed award-winning techniques but have also taught artists at different stages of their journey. How has teaching others shaped or challenged your own practice, particularly when exploring concepts of mystery, personal symbolism, and storytelling in sculpture?

I believe that teaching and learning are two inseparable parts of the same process: one of continual growth and enrichment within your chosen field. When teaching, I strive to understand my students’ needs and to learn from their unique ways of discovering something new. I can learn about my students’ cultural backgrounds, which in turn enriches my own artistic practice. I teach group and one-to-one sessions for beginners and improvers who wish to explore the art of relief sculpture or develop their sculpting skills. The Westbury Arts Centre in Milton Keynes hosts these sessions—where all the creative magic happens.

CAROL FOULGER

Congratulations Carol, Your work is driven by the atmosphere and energy of expanding urban environments. How do you translate something as fleeting as changing light or emotion into a lasting visual form on canvas?

I look for moments that speak to me. It could be a group of people standing by or a bus going past. Something that shows life, even if it appears to be mundane. When I go into London I like to vary the times of the day, different times of the year. Weather, the seasons, the time of day all affects light; so much so I could paint the same scene several times and each time would give me a different feeling and emotion. I want my paintings to capture a fleeting glimpse of life in the city.

You describe wanting to capture the “heart and soul” of a place. Can you share a moment in London that deeply moved you and became the spark for a particular piece in your lockdown collection?

I was on a photographic trip with my sister-in-law, and we ended up at Battersea Power Station. They were nearly at the end of the renovations. I fell a little bit in love with the building that day. The symmetry in the architecture, the impending shadows of the four chimneys looming. I loved the fact that it was being repurposed but was not losing any of its historical appeal. It was the rebirth of this iconic building. New life was being breathed into it and that excited me. It inspired me to paint “No22-The Icon” and “Battersea”.

Lockdown led you to rediscover the city through absence. How did that period reshape your understanding of vibrancy, and in what way did it change your artistic approach moving forward?

I was watching a news reel during lockdown that showed Regent Street completely deserted. I knew I had to capture this moment on canvas. It occurred to me that I was painting living history and this led me to want to capture as much as I could about our glorious city. It was then that I started to really look. The beauty in the architecture, the harmony between different periods in history, the changing landscape. I then became just a little bit obsessed with cranes in the skyline! I always look for that sign of evolution when I paint!

Your paintings aim to evoke emotion and a shared sense of belonging. What kind of journey do you hope a viewer experiences as they move closer to your work and begin to read the layers of colour and atmosphere?

My paintings, like life, are all about layers and detail. I love the impasto and sgraffito effect. The Sennelier Abstract acrylic range is perfect for that. For me, it is a way of creating depth and atmosphere, with different layers of society, history and architecture within. I want the viewer to be swept along in the memory of what that place means to them and be transported back to the sights, sounds, smells and emotions of being in that place.

DAVID KIRKMAN

Let us start with congratulations for your two winning submissions. Your work captures a striking balance between chaos and calm. How do you know when a painting has reached that perfect point of tension — when to stop adding and simply let it “be”?

That balance is what I’m always chasing. I start with no plan or reference; I paint how I feel. As the layers build, the piece starts to speak back to me; it connects with the emotions I’m feeling in that moment. That’s why I work fast, almost trying to keep up with my thoughts. Then suddenly it settles — the chaos softens, the colours breathe, and I feel calm. That’s when I stop. If I push past that, I lose the honesty that made it real. When I feel at ease in my body looking at it, it’s finished. Life’s full of contrast, I just capture the ones in my head in paint.

As a neurodivergent artist, your process is deeply instinctive. How do your sensory experiences or moments of intensity translate into your choice of colour, texture, and rhythm on the canvas?

Being neurodivergent means I feel everything deeply; sound, light, emotion, texture. My process is instinctive, so I don’t plan it, I feel it. When I’m energised and positive, my colours are bolder and cleaner, textures lighten, and metallics appear. When I’m tired or need calm, the work slows down, it has more texture, softer lines, stronger contrasts. I see the chaos of being neurodivergent as a strength. It gives my work energy, emotion, and honesty. Having AuDHD and also navigating my own mental health struggles, inspires not just how I paint, but why. It's the reason I create bold statement pieces that make people feel seen and uplifted.

Many of your pieces feel like emotional landscapes — raw yet hopeful. Do you see your art as a form of self-therapy, or more as a visual language for connection and understanding with others?

People do sometimes see landscapes, skies or seas in my work. I love that. I want them to see whatever they need to. For me, abstract art is not about dictating or challenging what someone sees, it’s about emotional connection. Painting began as therapy for me, a way to quiet the noise. Now it’s also a language for connection. If someone finds a landscape, a memory, or a mood in it, that’s the magic. The most important thing we create as an artist, is a smile. My job is to make honest work. The viewer brings the rest, that's where hope, escape and joy come in.

Winning the Galeria Moderna Invitational has placed your work in an exciting spotlight. How do you see this moment shaping your next chapter — both creatively and personally?

I’m genuinely grateful to have won this. It feels like an important step in my journey and I hope it helps my work reach more people who connect with its message. This year I held my solo show Mind Fizz and I’m proud to be represented by galleries who really believe in what I do. Looking ahead, I want to keep growing, pushing myself creatively and working with more galleries that share my passion for art that uplifts and connects people.

DAVID NEVE

Congratulations David, your work often explores tranquillity within motion and emotion within stillness. How do you find that balance between technical precision and emotional resonance when composing a shot?

I most often have to go into the scene or idea without any camera to see what the scene is telling me personally. I am continuously reminding myself to slow down due to my autism. The reworking of my technical thinking made me see that by manipulating the technical side to create the final work from the main visual concept, I opened more of the world in front of me, which went into a deeper emotional response. When this happens, I feel I have been successful with both the work and the scene I had been in and finding a voice for myself and that scene.

You’ve mentioned being inspired by legends like Don McCullin, Ansel Adams, and Hiroshi Sugimoto. What have you taken from their approaches and how have you shaped those influences into your own visual voice?

I felt McCullin’s war history still in his landscapes through the composure and the graphic contrasts of the lighting and tones, yet like Ansel Adams the balance of the landscapes feels calm and peaceful. Sugimoto’s wax works of well known historical figures opens the depth of what those figures had been through when they were in existence and simplified to understand.

Their influences together helped me to understand how I can find a way to build keys to unlock the depths of my mind and to help me communicate better with the life around me.

Much of your work seems to invite viewers to slow down and truly see. In today’s fast-paced world, do you think photography can help people reconnect with stillness and self-reflection?

Today’s very fast paced lifestyle where technology assists us getting jobs done yet it is eroding and changing how we see life, and I feel it’s making our lives move too fast losing the most precious part of all life, time itself. Slowing down time will allow us to think more and have a better, clearer understanding of what people truly want in their lives. If a viewer looks at my work and starts to explore their own thinking, evaluation and interpretation of what they see - which helps them to relook at life and inspiration, then I feel I have succeeded in reaching out to help other people.

From early recognition by the Royal Photographic Society to exhibiting with Galeria Moderna, your career has evolved impressively. Looking ahead, what new directions or themes are you most excited to explore in your future photography?

I’ve started to look into preserving the most successful works in a book to help inspire future generations. I have also been working on a special project since 2017 of my friends Ben and his sister Milli who are both athlete swimmers with special needs as they have the same as myself autism and with other health issues of which they have won golds and special awards of recognition in The Special Olympics and competitions across the UK as part of their team The Special Olympics City of Hull and defying the serious odds against them.

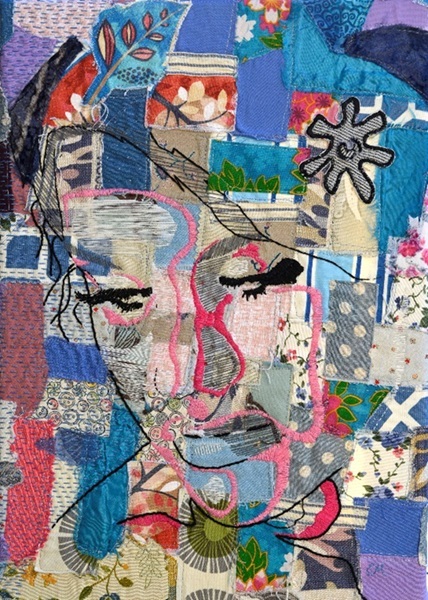

ESTHER MONTERO

Congratulations on becoming one of the winners of the London invitational, your work beautifully merges the tactile intimacy of textiles with the depth of portraiture. When you begin a piece, do you see the figure first in your mind or does the fabric itself guide the direction of the artwork?

Thank you so much, it is an honour to be one of the winners. I work in both ways. The most exciting is when I see something in the fabric that suggests a story or a figure within its pattern. In that case the fabric guides the development of the artwork, which evolves organically as I work on it. Other times I start with an idea or a reference image that I feel connected to and compelled to interpret in textiles. In those cases, the process involves a careful selection of fabrics and the style or technique that will help me to achieve the feeling or to create the narrative.

You’ve mentioned the “slow and intentional” nature of your process — stitch by stitch, a story unfolds. What does that meditative pace bring to your creative expression that perhaps faster mediums cannot?

When I start a piece, I have just an initial inspiration or idea, and it is through the slow process of hand stitching and responding to the fabric qualities, that I develop the piece organically. It is like having a placid conversation with the materials, I get the opportunity to think about the character and the story and new ideas may pop up and change the direction of the artwork. I may introduce details and symbolism that add depth and meaning. I feel that with faster mediums I wouldn’t get that intimacy with the materials and the character I am portraying.

You breathe new life into discarded fabrics, transforming them into deeply expressive works. How does this commitment to sustainability and re-purposing influence the stories or emotions you aim to convey through your art?

It can impose limitations which sometimes require a lot of thought when developing my artworks, as I need to adapt to the materials I have at hand. This can be frustrating sometimes but also stimulating as it can lead to exciting and unexpected results. I enjoy spending time looking at my materials and trying to imagine the ideas or emotions they could transmit. For example, a bag of small scraps of fabric suggested “fragmentation” and later inspired the basis for my winning artwork “Absence,” where I used a fabric collage as background to convey the idea of fragmented memories.

As one of the winners of the competition, and with your growing recognition in the textile art world, how do you see your practice evolving in the coming years — do you envision new directions, collaborations, or themes emerging?

I see my art practice as a long-term journey of self-development. My immediate vision is to keep learning and refining my skills, exploring the themes of identity and human experience but pushing the use of my materials to create more expressive characters and richer narratives. I am interested in experimenting with 3D elements to bring my characters closer to the viewer, explore full body portraits and working at bigger scale, which may open new directions. I feel I am just scratching the surface of what this medium can offer, and it is exciting to see the world of possibilities ahead.

LUCIA BABJAKOVA

Congratulations, Lucia! Your work is known for combining abstraction with representational forms, often using bold colour, symbolism and realism. How do you decide when a feeling or concept should be communicated abstractly versus anchored in recognisable imagery?

I usually use recognisable imagery when addressing a particular idea that I would like the viewer to feel something about and hopefully think about too. Or when I like something and want to paint it or when I tune in to myself to let the images appear. It's not about expressing my emotions but hopefully stimulating the viewer’s. Abstraction is obviously broader, perhaps touching the subconscious more if it’s done well as it is not restricted by narrative. That’s why I often combine both where the background is quite abstract, but there is also a recognisable imagery to create a synergy.

You’ve spoken about themes of freedom, injustice, and peace as central to your practice, shaped in part by your experience growing up under communism in former Czechoslovakia. In what ways do these personal histories influence the visual language of your work today?

Communism, for me, meant being watched, rigid bureaucratic rules and police implementing them. An underlying everyday oppression, a general fear of anything different or individual. I felt it never ended in 1989, it just shifted its shape and now I see the same pattern spreading. This theme of darkness and oppression beneath the surface, but also light and a universal energy of hope and peace is a thread through my work. The latest works are more political, reflecting/showing oppression and aggression towards people, animals and nature that we still see today, even more.

Having lived and exhibited across multiple European countries before settling in Shoreham-by-Sea, how has this cultural journey influenced your palette, symbols, or approach to storytelling within your paintings and drawings?

I’ve always had a strong sense of colour and how I wanted to interpret what I saw. I'm not sure travelling itself had much influence on my artistic vision apart from building a visual library in my mind. It was more the fact of leaving the restrictive atmosphere of my city and seeing some of the great original art for real that was uplifting and encouraging. In the end, everything you look at is blocks of colour with some lines, and you should forget what you know about the tree when you paint the tree.

Your pieces often use colour not just as aesthetic choice, but as an emotional force. When composing a work, does a specific colour arrive first as a feeling you need to express, or does the narrative emerge and pull the palette into place afterward?

When painting something in real life, the shape is already there and I see colours emerging to change the ordinary scene into something new, to give it an edge. When I have an idea that I want to paint, it’s not just an image in my mind but also an idea of an emotional impact I’d like to create which comes with the choice of colours. With abstract art, I still have some idea of the impact I’d like it to have. I’m expressing my view and understanding of the world, not my emotions at the time.

MARTA SOOKIA

Congratulations, Marta! Your work spans both abstract and realist expression — how do you decide whether a concept is best conveyed through a figurative form or through abstraction, and do the two ever merge as you paint?

When I first started to paint, I would focus only on realist paintings. The pieces that I created would consist only of figurative forms. However, at the back of my mind, I was simultaneously attracted to abstract art. Over time, I began to realise that I could explore the possibility of merging the two styles, and so I began to include abstraction into my realistic paintings only a few years ago. In my most recent pieces, I like to keep the subject refined but the background abstracted.

Your Polish heritage remains a strong part of your identity even after two decades in the UK. In what ways do your culture, traditions, or early memories manifest themselves in your visual language, colour choices, or subject matter?

I have always been a strong believer in maintaining my own culture and traditions as part of my heritage whilst growing up. In this way, I have remained true to my own self and continued to be a genuine version of myself without being influenced by external parties. My early childhood years growing up in Poland with a positive mindset have shone through with the positive colours used in my pieces and the positive messages that I am trying to portray in my pieces.

You describe painting as a deeply sensory experience, where closing your eyes heightens sound, scent, and emotion. Can you walk us through how a moment in nature — a forest walk or ocean swim — translates into brushstrokes, textures, or movement on canvas?

When you close your eyes, you close off one of your many senses but then your other senses are heightened particularly sound, smell and touch. Imagine a tree.......the rough bark that is a deep brown in colour and the smooth dark green leaves of the trees within the forest.......the wind blowing and the feeling of peace and tranquillity. These then become easy to translate onto a canvas as smooth and continuous brush strokes. With the ocean you could picture a gentle crashing of the waves onto the beach and use light blue and white colours with a slight rough texture to depict the actual feeling of each wave.

Your Garden Room studio, built in 2022, has enabled you to create consistently and with freedom. How has having a dedicated creative space changed your artistic rhythm or the ambition of the pieces you now feel inspired to produce?

It has been a turning point in my life. Before I had my art studio, I painted only a few paintings per year. Trying to squeeze in-between the fridge and the dining table in my house. By the time I had set up the easel, pallet and all the painting materials there wasn't much time to paint, especially as my family were using the same space for daily routines. Once the garden room was built everything changed for me. I have been painting almost every day since, producing new artwork every week. It is so important for artists to have a dedicated space to create, not only for logistical reasons but also because it helps to awaken the creative spirit behind closed doors without any form of distraction.

MAUREEN GRAYSON

Congratulations on your success, Maureen! Your work captures the volatile dance between nature and abstraction — when approaching a new piece, do you begin with a specific natural moment (a shift in light, a change in weather), or does something else guide the direction of the landscape?

Approaching a new piece of work can vary in application. It can often be something as simple as the substrate that sparks an idea and the palette will emerge as a natural progression. My first choice when building a landscape will most likely be on paper. I favour its versatility and forgiving nature over all else. Being predominantly a creature of the night, I choose the early hours of the morning in which to create. The silence and darkness present the ideal environment for translating my moods and emotions into the bigger picture.

Your mixed media process involves crafting your own collage papers and layering textures to build depth. Can you share a moment when an unexpected material or mark entirely changed the atmosphere or narrative of a piece?

My collection of collage papers have recently undergone a massive clear-out. It's been a similar fate for materials I've gathered, then deemed unworthy of further existence. Despite the fact they'll all be used in my layering process to build textures, there's a limit as to their viability.

Occasionally, however, an element of total surprise will emerge, albeit the result of a happy accident! The time I managed to spill water over an inkjet colour copy produced the most bizarre stained paper I'd ever seen. I used it as collage to depict the impression of reflection in a woodland pond.

You speak of memories, darkness, and fantasy blending within your abstract forms. How do you find the balance between mystery and clarity — leaving enough space for the viewer's imagination while still grounding your work in a resonant truth?

Admittedly, there's a fine line between mystery and clarity. I often find the two overlap to such an extent, I'm forced to pull back and reassess the vision. As a helpless fantasist, this poses endless dilemmas. While I want to remain in my own true space, there's always the fear of losing my audience lurking somewhere in the background. Finding that balance has often resulted in sheer abandonment with an inner voice suggesting I simply trust the viewer to share my wavelength! It can come down to something as simple as, you feel my work or you don't.

As an artist deeply moved by nature's unpredictability, how do light, temperature or seasonal transitions affect not only your palette, but also your rhythm in the studio — do you find yourself working differently in winter than in the glow of summer?

As much as I'm inspired by dark skies and tempestuous weather conditions, I require periods of intense light to lift my mood. This can be anything from flashing LEDs in a floor lamp to the natural sun shining down through my studio skylight. Light and darkness can double as a mental state switching the creative flow on and off at random. I'm at my most productive when I find the happy medium between the two. I was born on the summer solstice, a moon child. This sums me up precisely.

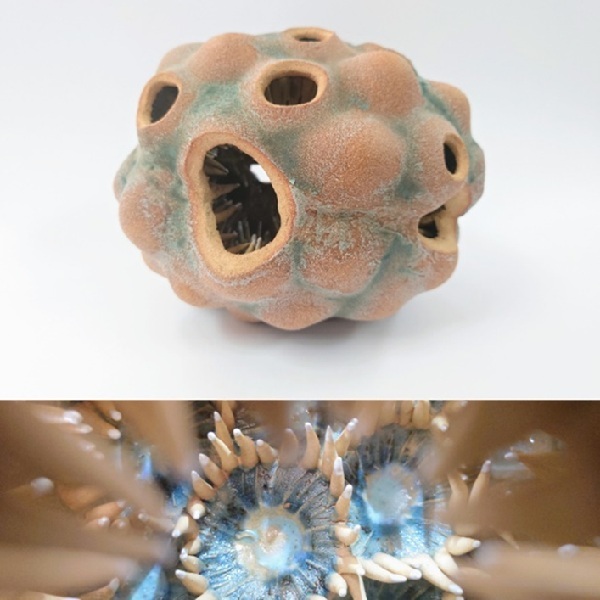

PAULA ARMSTRONG

Congratulations, Paula! You describe clay as something that continues to surprise and challenge you even after nearly thirty years — can you share a moment in your practice when the material pushed back or behaved unexpectedly, leading you to discover something entirely new in your process or yourself?

One of my earliest sculptures took far longer than expected. The delicate inner forms refused to stay where I wanted them — collapsing, cracking, or coming unstuck. I’d combined two different clays at slightly different drying stages, and they simply weren’t ready to cooperate. It taught me a great deal about patience, timing, and how materials respond to each other. More importantly, it reminded me that clay isn’t something to control. It has its own will and voice. Sometimes persistence is useful, but it’s flexibility that allows both the piece and the maker to evolve. You can’t always be in control, and that’s the beauty of it.

Your sculptures centre around connection — between maker and material, and between artwork and viewer. How do you consciously foster this sense of shared discovery during creation, or do you intentionally leave space for the viewer’s own interpretation to complete the dialogue?

When I make, it always feels like a conversation between myself and the clay. I might begin with a clear idea, but the material inevitably adds its own thoughts along the way. That exchange is what keeps the process alive and engaging. My inspiration forms the first chapter of each sculpture’s story, but I always leave space for the viewer to write the next one. Everyone brings their own perspective — shaped by memory, experience, and emotion — and I find that dialogue endlessly fascinating. Some people see hope, others strength or vulnerability, and I treasure every response.

With a career that spans exhibitions from London to Venice and the Florence Biennale, how does showing your work internationally influence your understanding of universal connection versus culturally specific interpretations of form and emotion in ceramics?

I’ve always seen things from an international perspective. Born in Canada and based in the UK since childhood, I’m very aware of how cultural references can sometimes create distance. That’s why I draw from nature — its patterns, textures, and structures are a language we all share. My work often abstracts these familiar forms into something that feels recognisable yet universal. When exhibiting internationally, I’m always struck by how people from different cultures respond in similar ways. Those emotional connections prove how instinctively we understand ideas of growth, protection, and transformation — wherever we come from.

You speak passionately about teaching and witnessing the magic of students opening the kiln. How does nurturing creativity in others feed back into your own artistic evolution, and does the act of teaching ever shift the way you approach risk, play, or curiosity in your own studio practice?

Teaching constantly reminds me to stay curious. My students bring fresh ideas, new questions, and the kind of fearless experimentation that reignites my own creativity. Their excitement about trying unfamiliar techniques or solving tricky builds pushes me to keep learning too. I love watching someone open the kiln and light up at what they’ve made — even when it’s imperfect. That joy is what making should always be about. Teaching has made me braver with my own risks and more forgiving of mistakes. If nothing’s going wrong, I’m probably not stretching myself enough. Teaching keeps me grounded, inspired, and endlessly grateful for what clay has to teach us.

Huge thanks to Galeria Moderna and all of the winning artists!

Feeing inspired?

Visit the Galeria Moderna website to watch a stunning 3D spatial video showcasing all the artists from this incredible show. www.galeria-moderna.com